Would supply management work for pork industry?

“Would You Rather” is an age-old game. My kids have a favorite. Would you rather be super-fast or super-strong?

I heard a good one from a college student. Would you rather have a sneeze that never comes or an itch you can never scratch? Some are deeper. Would you rather have more time or more money?

Really good questions for “Would You Rather” reveal surprising insights about those answering them. The best ones make people think about what they value most. With pork producers facing some of their toughest economic times ever, asking “Would You Rather” may provide some perspective.

Free market or supply management?

USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service tallied the Dec. 1U.S. all hogs and pigs inventory at 74.97 million head. This is the fourth-largest Dec. 1 total inventory on record going back to 1963. Large losses and producers not trimming production both fuel chatter about alternative ways to trim supplies to boost prices.

Supply management attempts to match supply with demand. Typical tools are:

- regulating output with production quotas

- basing producer prices on input costs, plus a profit margin

- restricting imports with tariff-rate quotas

- abdicating export markets to lower-cost suppliers

Supply management is counter to the “invisible hand,” which economist Adam Smith introduced in his book “The Wealth of Nations” in 1776. Smith theorized that in a free-market, unobservable forces efficiently push supply and demand to an equilibrium. The market becomes self-regulating. Adjustments that companies make as they seek profits help create efficiencies that lead to the market equilibrium. Unfortunately, short-term market imbalances can occur.

Supply management, too, has challenges. Production quotas prohibit operations from upping output to spread overhead expenses over more production. This hikes per-unit costs for efficient producers and keeps less-efficient producers in business.

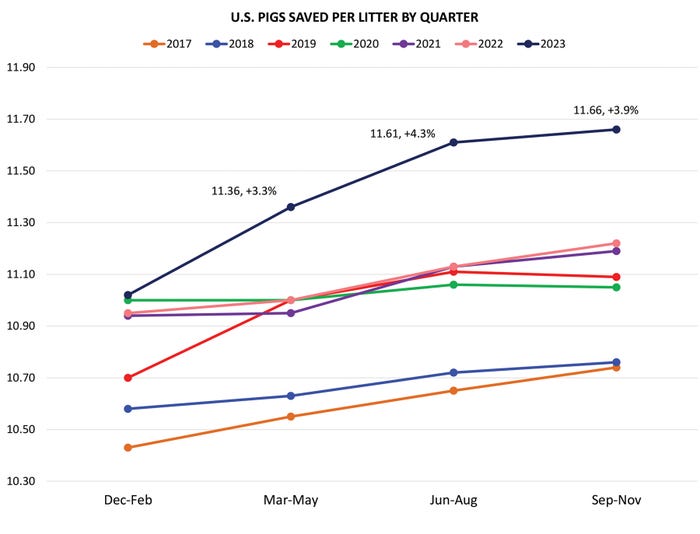

Productivity of the U.S. swine breeding herd continues to rise. From September through November, sows on U.S. farms weaned an average of 11.66 pigs per litter. That’s a record and a 3.9% increase from 2022.

A shift to supply management would remove incentives to continuously improve. Building a profit into the cost-of-production formula perpetuates the status quo. Producers may become less receptive to innovation.

Under supply management, production quotas become marketable assets for existing producers. Intentionally or not, quotas are also a large barrier to entry for beginning producers because new producers need extra capital to purchase the production quotas.

Supply management generally seeks to equate domestic supply with domestic demand. Even if there was excess supply, relatively high domestic prices under cost, plus supply management, would price producers out of export markets. Much of the growth in U.S. pork production during the last two decades is due to higher exports.

Weakened or non-materialized demand?

From 2019 into 2022, rising pork demand fueled expansion. Consumers’ dollars flowing into the industry drove profits and new investments. Even when demand is strong, an industry will not always be profitable for every producer, nor will it be profitable every year.

Now domestic retail pork demand has eroded year on year for six consecutive quarters. Consumer income, prices of substitutes and complements, and tastes and preferences are all demand determinants. Household budgets benefited from stimulus payments, debt forbearances and increased savings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those benefits have come to an end. Total household debt continues to reach new heights led by mortgage, credit card and student loan balances. Servicing debt curtails spending.

When income falls, people generally buy less. Inflation has the same effect. It erodes buying power — even if consumers’ nominal income holds steady or rises slightly. Less buying power weakens demand.

When demand decreases, consumers are not willing to pay a higher price, after removing the influence of overall price inflation, for the same quantity or even for a smaller quantity. Sagging consumer demand creates a profit squeeze all the way down to producers at the beginning of the supply chain. Losses force the industry to contract.

Domestic and international demand determines what level of pork production is needed. Rising demand would be a catalyst for profits and growth.

More risk or less?

Making money generally involves taking risks. Higher profits are typically associated with higher risks.

The pork industry risk-return trade-off may currently seem out of balance. But you need to remember the proverb “You have to be in it to win it.” That is one reason why pork producers are reluctant to trim production ― despite sizable losses.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!